A ray consists of two components:

-

an origin \(O\) of type

Point3D; -

a direction \(\vec\Delta\) of type

Vector3D.

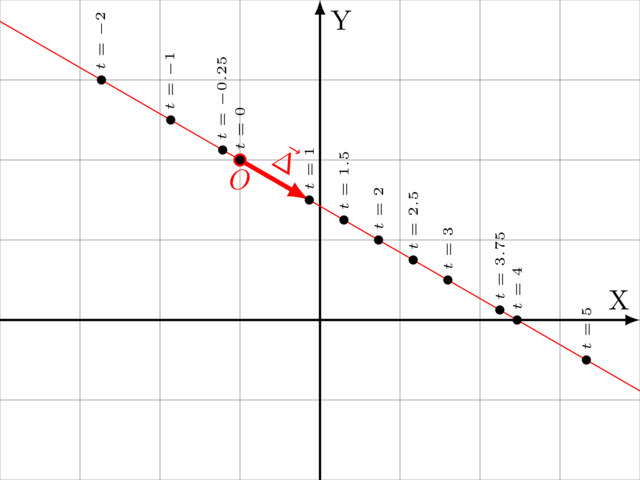

The ray is the entirety of points that lies on the line that goes through \(O\) and has orientation \(\vec\Delta\). All points on the ray are represented by the thin red line on the above figure.

Mathematically, a ray is written as follows:

where \(t \in \mathbb{R}\).

Each point on the ray has a unique \(t\)-value associated with it. \(t\) represents the number of "steps" of size \(\Delta\) one has to make starting at the origin \(O\). For example,

-

\(t = 0\): take zero steps starting in the origin \(O\). You obviously end up in \(O\).

-

\(t = 1\): take one step away from \(O\) in direction \(\vec\Delta\).

-

\(t = 5\): take five steps away from \(O\) in direction \(\vec\Delta\).

-

\(t = -1\): take one step in the opposite direction of \(\vec\Delta\).

In the ray tracer, the ray’s origin will often coincide with the eye. If \(t > 0\), the point is in front of the eye; if \(t < 0\), the point is behind the eye. Making this distinction is very important in ray tracing: you will only be interested in points in front of the eye.